New Boston Historical Society

New Boston, New Hampshire

A Walk Through the New Boston Cemetery

Drive up Meetinghouse Hill Road from the center of New Boston village and take your first right onto Cemetery Road to visit the hilltop cemetery which has been the town's primary burial ground for 250 years.What will you see? Here are photos and stories about some of the gravestones in the cemetery, to encourage you to take a closer look the next time you visit.

Note to genealogists: if you want to search by name for some of the permanent residents of the New Boston Cemetery, the FindAGrave.com database contains over 2,500 entries for New Boston, entered by volunteers. In 2018 we updated our Links page with a gravestone database. Look for the "Cemetery and Burial Ground Records" and the cemetery maps documents.

The First Meeting House and Cemetery

The First Meeting House and Cemetery

In 1756, when there were only 59 people in New Boston including men, women and children, a committee was appointed "to fix a proper place in or near the centre of the town for the public worship of God; and also for a public burying place, as they shall think most suitable for the whole community." Lot 79 was eventually selected, and this is where the cemetery is today.

The first meeting house was built around 1765-1767, and its site is marked by a boulder in the cemetery. According to one report, the meeting house stood in a bleak place and was never furnished with a means of warming. Therefore a small "session house" was built next to it with a fireplace that could be lit for Sunday meetings.

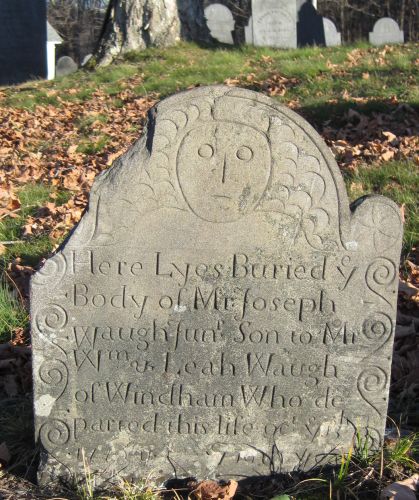

The oldest gravestone which can be found in the cemetery today is that of New Boston's first town clerk, Alexander McCollum, who died in 1768. McCollum's stone is very plain; let us look instead at the interesting artwork on the gravestone of Joseph Waugh, who died two years later.

During Colonial times, each stone carver had his own unique style, and it is possible for experienced researchers to recognize the individuals who carved some of the gravestones.

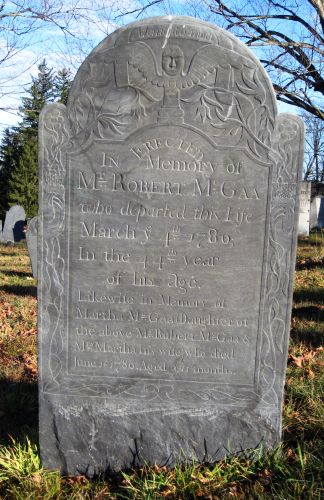

The earliest gravestones in the cemetery are made of slate, which was the most popular material for gravestones in the 1700s. A quarry in Harvard, Massachusetts about 40 miles due south of New Boston was a source of the highest quality blue slate for gravestones.

Robert McGaa's slate from 1786 is a very fine example. The details are as sharp today as when they left the stone carver's workshop over two hundred years ago. Later stones were made of marble, which as we shall see does not weather as well as slate.

Let's look at a few more examples of slate gravestones:

Nine year old Lettice Crombie, who died in 1789, has both a headstone and a footstone, arranged as one would the headboard and footboard of a bed.

The stone carver appears to have chiseled out the recessed rectangle around her name on the footstone to correct an error or replace another name.

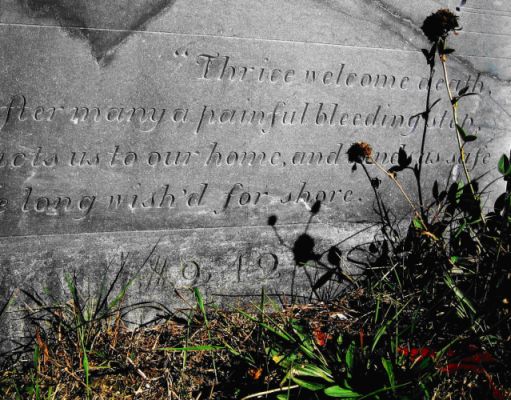

As the ground level subsides, Janet Dickey's 1811 gravestone now reveals its $9.42 price tag.

Two sides of the same stone

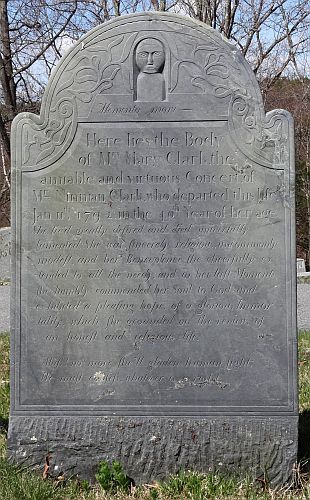

1. It's rare to find a slate gravestone carved on both sides. (An example of New England thrift, perhaps?)

2. Because Mary died in 1790 and her husband Ninian died almost 40 years later in 1828, this stone captures a change in gravestone art.

Mary's 18th-century carving contains themes of nature (flowering vines) and the "soul effigy" or human face that you see in the photos above.

Ninian's carving contains themes that were popular in the 19th century: a willow tree over an urn, and columns on either side of the inscription. In the 1800s, there was renewed interest in the Greek and Roman civilizations, and this encouraged artists and architects to borrow from classical designs and materials. We'll see more columns appearing in gravestone art, and the use of marble for gravestones and monuments.

Marble

In the 1800s, marble became the most popular material for gravestones. More expensive than slate, marble was easier to carve. Unfortunately, marble does not weather as well as slate, and acid rain has blurred the carvings and text on many gravestones.

The 1800s also saw a transition from the folk art seen in the soul effigies on the slate gravestones to more formal designs mass-produced in larger workshops.

The Buxton gravestones from the late 1800s show two popular symbols: the hand and the anchor.

Most people could read by the late 1800s when Ira Buxton's two wives died, but symbols on marble gravestones were very popular. In the photo above, the hand points to heaven, where it is hoped that the soul of Emma Buxton now resides. The anchor on Mary Buxton's stone does not indicate a nautical connection. It symbolizes hope, as in the New Testament quotation "which hope we have as an anchor of the soul" (Hebrews 6:19).

Elsewhere in the cemetery you may see a clipped rosebud on the gravestone of a young child or a sheaf of wheat on the gravestone of someone who was "harvested" late in life.

Neither Slate nor Marble

Several gravestones in the New Boston cemetery are made of cast zinc.

These hollow "white bronze" monuments were produced from around 1875-1910.

From a distance they look like granite. The metal is corrosion-resistant but brittle.

Gravestones of the 20th and 21st Centuries

This interesting stone marks the grave of a young woman who died in a motor accident in 1925.

A $20,000 scholarship fund at Vassar was given in her name. This was a considerable sum of money at that time.

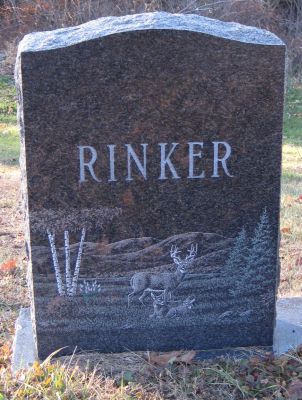

Detailed drawings are made on polished granite gravestones by sandblasting or laser engraving.

Two Stories about New Boston Gravestones

The Violinmaker's Wife - A gravestone helps with historical research.

The Violinmaker's Wife - A gravestone helps with historical research.

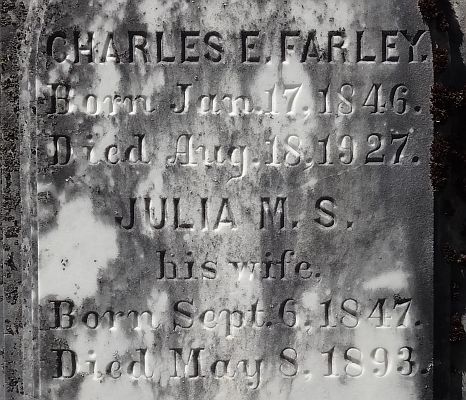

Charles and Julia Farley lived in the house on River Road which still stands next to Dodge's Store. Charles had a workshop in this house in which he made violins. (One of his instruments is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.)

While researching Charles Farley (1846-1927) for another project, I read that he left New Boston after his wife drowned in the river behind their house. The Piscataquog River, which is quite shallow in late summer, can be deep and turbulent during spring floods. I could find no more information about the Julia Farley incident.

When I was in the New Boston cemetery taking photos for this web page, I stumbled across the Farley family monument and noted Julia's date of death: May 8, 1893. Coincidentally, we happen to have notes about the weather for this month.

One of the key events in town history was the official opening of the New Boston Railroad in June of 1893. In May of 1893, workmen were hurrying to complete a new bridge to connect the railroad depot to the village center.

A newspaper article reports: "May 13, 1893 - The heavy rain of May 4th caused the Piscataquog to overflow its banks near the terminus of the railroad... There were many spectators watching the new bridge and at one o'clock an immense tree stump was seen rushing along on the foaming water towards the bridge, which when it hit carried the iron work about 200 feet before it sank." The Depot Bridge was repaired, but we now have an idea of what the river must have been like when poor Julia fell into it!

Sevilla & Henry - A 19th-century murder.

Sevilla & Henry - A 19th-century murder.

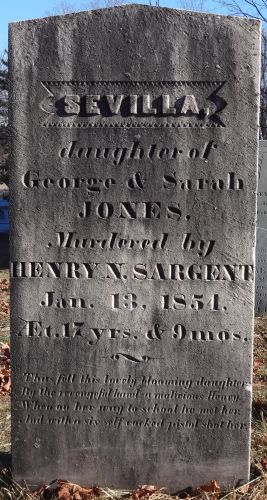

The inscription on New Boston's most notorious gravestone reads:

SEVILLA, daughter of George and Sarah JONES.One winter morning in 1854, Sevilla Jones was walking to Schoolhouse #3 near Joe English Hill with her younger brother Plummer.

Murdered by HENRY N. SARGENT, January 13, 1854.

[At the age of] 17 years and 9 months.

Thus fell this lovely blooming daughter

By the revengeful hand - a malicious Henry

When on her way to school he met her

And with a six self-cocked pistol shot her.

They were approached by Henry Sargent, a 23-year-old woodcutter whose family lived near the Jones family. Henry loved Sevilla and he believed that she had "given him encouragement." However, he had a rival in another young man named Bartlett.

According to a long rambling note written in his diary, Henry believed that Bartlett's mother had conspired with Sevilla's mother to convince the girl to prefer Bartlett. "She proved false, by bad advice," he wrote.

Henry used an Allen & Thurber pepperbox revolver to shoot Sevilla four times, killing her instantly. He then shot himself, with less immediate success. It has been said that a doctor was fetched, but he was so angry with Henry that he wouldn't treat Henry's wound and let him die.

As for the curious epitaph on the gravestone — some say that it was written by Bartlett's mother.

See "Sevilla and Henry" for more details.

I would like to thank my sister-in-law and my daughter for their technical advice and patience during visits to the cemetery.

They're both "taphophiles" - people who are interested in cemeteries and gravestone art. -Dan R.